12 Principles for Climate-Centric Behavior Change Communications

CNCA 08/09/19

By Michael Shank

This article is available to download as a PDF document and may be used as a resource to help guide your communications, campaigns or community engagement activities. It is based on the social impact research of ideas42.org and connects key psychological principles of applied behavioral science to the climate and sustainability work of CNCA member cities. Download a PDF version here.

In order to quickly move cities and towns towards carbon neutrality, one social science game changer that needs to be scaled up is behavior change communications. Few of the more technical game changers in our climate-leading communities— enumerated in Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance’s Game Changers report, for example — will be possible unless public and political will is mustered, mobilized and maintained over time.

This article delves into 12 behavioral science-based principles and psychologies to consider when rolling out sustainability initiatives in cities or communities of any size, especially efforts that require buy-in from a particular sector, be it public or private. These principles are well-known to the fields of sociology, psychology and behavioral economics (and packaged and explained succinctly by Ideas42) and will be helpful in thinking through how we apply them to our work in building consensus around, and communicating out, game-changing policy.

Whether you’re adopting a zero emissions standard for new buildings, building a ubiquitous electric vehicle charging infrastructure, mandating the recovery of organic material, electrifying buildings’ heating and cooling systems, designating car-free and low-emissions vehicle zones, empowering local producers and buyers of renewable electricity, or setting a city climate budget to drive decarbonization, these 12 principles offer useful guidance in the rolling out of any of the aforementioned game-changing strategies.

With each of the 12 principles and psychologies, I’ll take a look at how a city, town, or organization’s climate and sustainability initiatives are relevant within each principle of behavioral science and how they’re organized and communicated to the publics. Let’s begin.

#1 Choice Overload

There’s lots to do when it comes to climate policy, and it’s not uncommon to see websites advocating for myriad actions and initiatives — because, in all fairness, the work is massive in scope. Whether it’s big building retrofits, green energy installs, public transit improvements, waste management, bike lane build-outs, or household weatherization, there’s so much that needs to be pursued now. Not later, now. But is there a way to deliver this to users in a way that doesn’t cause choice overload? And is there a way to deliver, as Ideas42 put it, that decreases the number of choices presented and increases the meaningful differences between them?

There’s lots to do when it comes to climate policy, and it’s not uncommon to see websites advocating for myriad actions and initiatives — because, in all fairness, the work is massive in scope. Whether it’s big building retrofits, green energy installs, public transit improvements, waste management, bike lane build-outs, or household weatherization, there’s so much that needs to be pursued now. Not later, now. But is there a way to deliver this to users in a way that doesn’t cause choice overload? And is there a way to deliver, as Ideas42 put it, that decreases the number of choices presented and increases the meaningful differences between them?

For example, what if a city’s sustainability and climate webpages offered a featured action of the month? And it encouraged users to take that one action during that one month. And all of the city’s communications centered around that one action. And then, the next month, the city could roll out a new action that it wants residents to take. Residents who are ahead of the curve could always explore more actions: the city’s website could have in the background (and off to the side) an easy-to-navigate catalogue of the 12 actions (that run concurrently with the calendar year) that all residents can take to help the city and their homes/communities be greener, more efficient and healthier.

Exercise: Before moving on to the next principle, take a quick look at your communication materials to see if a user might feel choice overload and, as a result, feel too overwhelmed to take action. How could you simplify the site so that users are directed to one or two priority actions that they can take now? You can always rotate these through later without compromising your priorities or the urgency that’s needed to accompany these actions.

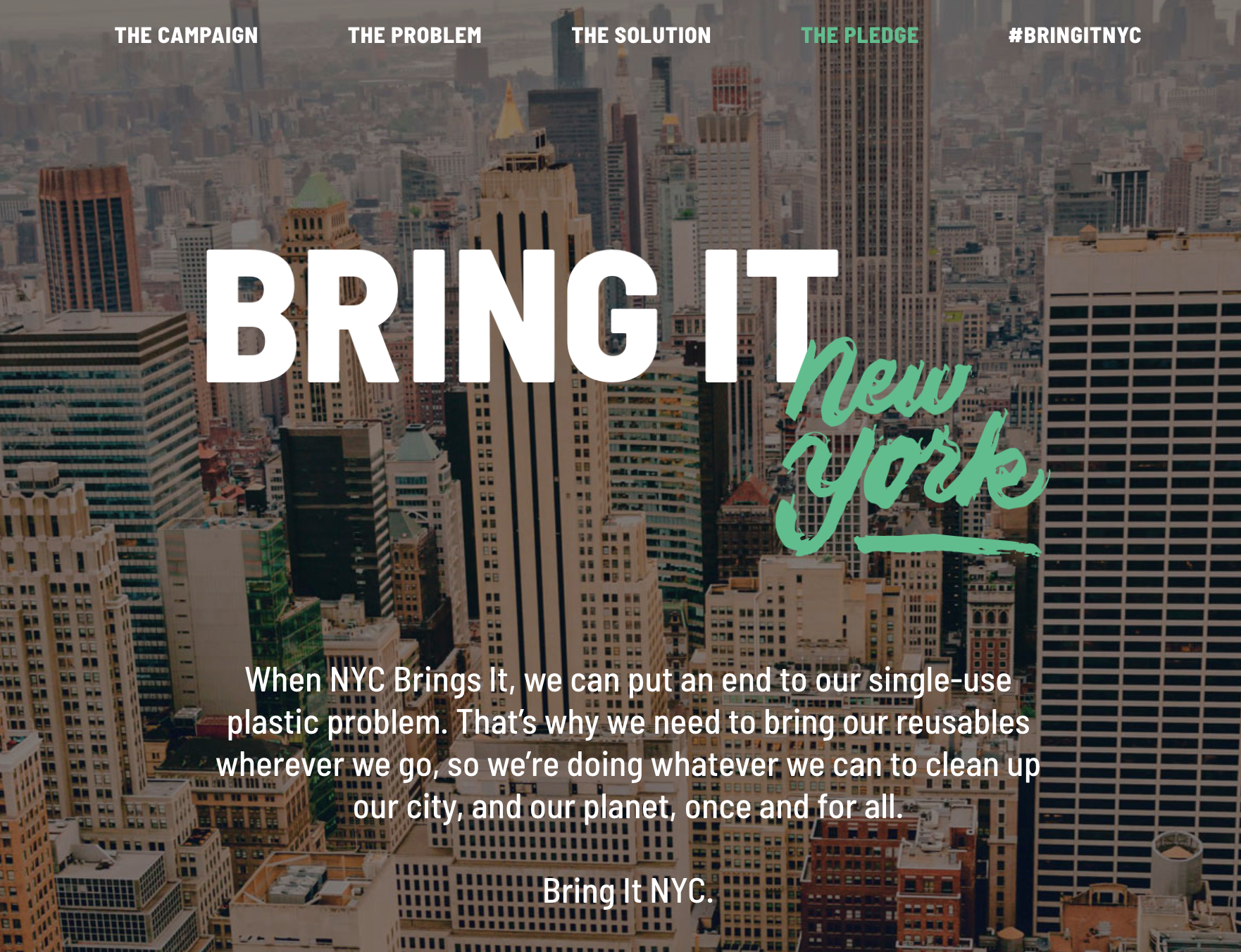

Example: New York City’s “Bring It” campaign has a singular ask – to bring reusables wherever one goes – and the entire website is devoted to that ask. It avoids choice overload by prioritizing and featuring only one ask, one activity, in this campaign. You can see on their website that even the navigation bar is avoiding choice overload, identifying one problem and one solution. It’s empowering for people to get involved in singular campaigns like this; the completion of the task feels more fulfilling when there’s not a laundry list of tasks that follow.

Example: New York City’s “Bring It” campaign has a singular ask – to bring reusables wherever one goes – and the entire website is devoted to that ask. It avoids choice overload by prioritizing and featuring only one ask, one activity, in this campaign. You can see on their website that even the navigation bar is avoiding choice overload, identifying one problem and one solution. It’s empowering for people to get involved in singular campaigns like this; the completion of the task feels more fulfilling when there’s not a laundry list of tasks that follow.

#2 Cognitive Depletion and Decision Fatigue

There’s plenty of research in the social science field on how fatigue makes for bad decision-making. Considering this, then, how are we reaching out to the community to build public and political will and are we cognizant of when and where they might be fatigued (and thus less equipped to support our climate initiatives)? And when we’re hosting events, are we bringing food (yes, sometimes it’s that simple) so that we’re enabling the community of decision-makers to be well-equipped to get on board a sustainability decision?

There’s plenty of research in the social science field on how fatigue makes for bad decision-making. Considering this, then, how are we reaching out to the community to build public and political will and are we cognizant of when and where they might be fatigued (and thus less equipped to support our climate initiatives)? And when we’re hosting events, are we bringing food (yes, sometimes it’s that simple) so that we’re enabling the community of decision-makers to be well-equipped to get on board a sustainability decision?

Mindful, also, of how many residents in our community are often underserved in their ability to receive and maintain proper nutrition, due to limited financial means and food deserts, how are we managing this food insecurity and working with other city departments to help ensure that the community has what they need? This is a great example of how social and environmental sustainability are interconnected and how we must work together to ensure the community has the resources they need to make the healthiest decisions they can make.

Example: Partnering with restaurants, bars and beverage companies can help with cognitive depletion and decision fatigue as Yokohama did here in their partnership with Starbucks for the “Nothing is Charming” campaign. The campaign was held inside Starbucks coffee houses to raise awareness about the benefits of using less electricity.

Example: Partnering with restaurants, bars and beverage companies can help with cognitive depletion and decision fatigue as Yokohama did here in their partnership with Starbucks for the “Nothing is Charming” campaign. The campaign was held inside Starbucks coffee houses to raise awareness about the benefits of using less electricity.

#3 Hassle Factors

This is a huge one for cities and communities everywhere. How can we make green choices easy for our community? If we want people to ride the bus more, bike more, eat more plant-based diets, waste less, weatherize more, and buy heat pumps and solar power, how do we make hassle-free or as close to hassle free as can be?

This is a huge one for cities and communities everywhere. How can we make green choices easy for our community? If we want people to ride the bus more, bike more, eat more plant-based diets, waste less, weatherize more, and buy heat pumps and solar power, how do we make hassle-free or as close to hassle free as can be?

Can we make it more enjoyable, more affordable, or more accessible? People might be more willing to undertake the effort and expense needed if they’re doing it in friendly company, with free food, while having a fun time. Think of a time when you needed help moving, painting, or constructing. You may have added some friends, some free food and some music and it was a little less onerous. The same goes for going green. If we can’t reduce the hassle any further (and let’s do everything we can to make it hassle-free), let’s at least make it fun, family-friendly, with free food.

Exercise: Let’s vet each of our sustainability initiatives to see how hassle free it is for a representative resident of the community. Are there ways that we can make any of these processes slightly less cumbersome? Recognizing that some of these green initiatives are heavy lifts — in terms of time or money spent — are there ways in which we can offset some of the hassle with positive reinforcement?

Example: Helsinki is making it easy for residents to discard waste with these convenient vacuum-sucking disposal systems. Not only does it make waste disposal near hassle-free for the resident, it’s also fun to do and avoids hassle-heavy trash bins that often fill up quickly and spill over.

Example: Helsinki is making it easy for residents to discard waste with these convenient vacuum-sucking disposal systems. Not only does it make waste disposal near hassle-free for the resident, it’s also fun to do and avoids hassle-heavy trash bins that often fill up quickly and spill over.

#4 Identity

Since not everyone considers themselves an environmentalist, how we do tap into and resonate with other identities that might be attracted to our climate policies? When we think of the myriad ways in which our communities self-identify, what are the principles that matter to these different identities? Parents, for example, would have, as part of their identity as guardians, a desire to keep their children safe from harm and to provide for their household. In that one sentence, we’ve covered health, security and economics. Are we mindful of this when messaging and mobilizing on our climate initiatives? And in the words of Ideas42, how do we “prime positive identities to encourage socially beneficial actions”?

Since not everyone considers themselves an environmentalist, how we do tap into and resonate with other identities that might be attracted to our climate policies? When we think of the myriad ways in which our communities self-identify, what are the principles that matter to these different identities? Parents, for example, would have, as part of their identity as guardians, a desire to keep their children safe from harm and to provide for their household. In that one sentence, we’ve covered health, security and economics. Are we mindful of this when messaging and mobilizing on our climate initiatives? And in the words of Ideas42, how do we “prime positive identities to encourage socially beneficial actions”?

Exercise: If we were to do a scan or audit of our climate and sustainability communication vehicles (printed materials, speeches, websites, social media, etc.), how are we being mindful of our community’s many identities and how are we tailoring our message to be respectful of and resonant with these worldviews? Ultimately, we want everyone to see our work and connect with it. That means we’ll want any and all of our behavior change-related communications to be super sensitive to the identities that are coming to our events, our websites and our action requests. Let’s make sure they see themselves in our work.

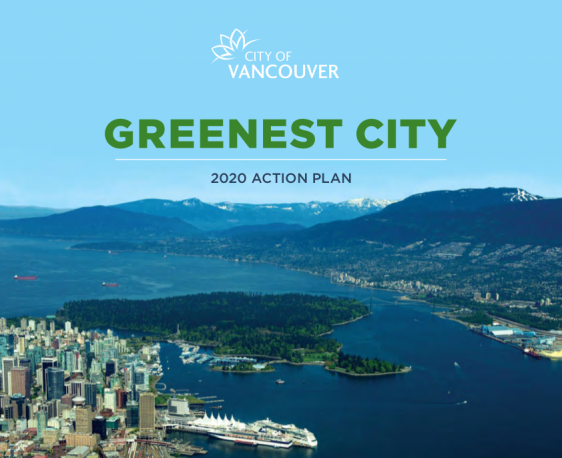

Example: Vancouver taps into city/resident identity and city/resident pride with their “greenest city” framing here. This identity framing appeals to people’s – and the city’s – competitive spirit and desire to be first.

Example: Vancouver taps into city/resident identity and city/resident pride with their “greenest city” framing here. This identity framing appeals to people’s – and the city’s – competitive spirit and desire to be first.

#5 Limited Attention

When our communities don’t immediately do what we ask them to do it’s not because they’re not interested. Perhaps they only heard it once from us, perhaps they never heard it at all, or perhaps other priorities took their attention at the time. How is the community hearing from us over and over and over again, in highly visible ways, so that amidst the limited attention spans, they’re hearing from us at least a half dozen times? Are we simultaneously using radio, television, billboards, community newspapers, community newsletters, local associations and advocacy organizations, religious halls, phone and email, text and other ways to communicate with the public?

When our communities don’t immediately do what we ask them to do it’s not because they’re not interested. Perhaps they only heard it once from us, perhaps they never heard it at all, or perhaps other priorities took their attention at the time. How is the community hearing from us over and over and over again, in highly visible ways, so that amidst the limited attention spans, they’re hearing from us at least a half dozen times? Are we simultaneously using radio, television, billboards, community newspapers, community newsletters, local associations and advocacy organizations, religious halls, phone and email, text and other ways to communicate with the public?

Mindful of our own limited attention spans, and being compassionately cognizant of all that’s taking priority in our community’s lives, how do we make it easy for everyone to hear from us, by repeating and reiterating our work through every possible channel that might reach them? While this may sound time-intensive (and it is), it’ll be necessary if we want to truly engage our community and transform policy. Surrogates and liaisons can be helpful here, as we don’t have all the inroads and we don’t always have the credibility as communicators that more local leaders might, so employ others if/when possible. But we have to reach our audience often.

Exercise: Taking an audit of the frequency of your city’s or town’s or organization’s climate communications, how and when are you repeating and reiterating and is it resonating? And if not, let’s pre-test and focus-group these messages to ensure that it’s the right wording and the right messenger for the right identities (per previous section).

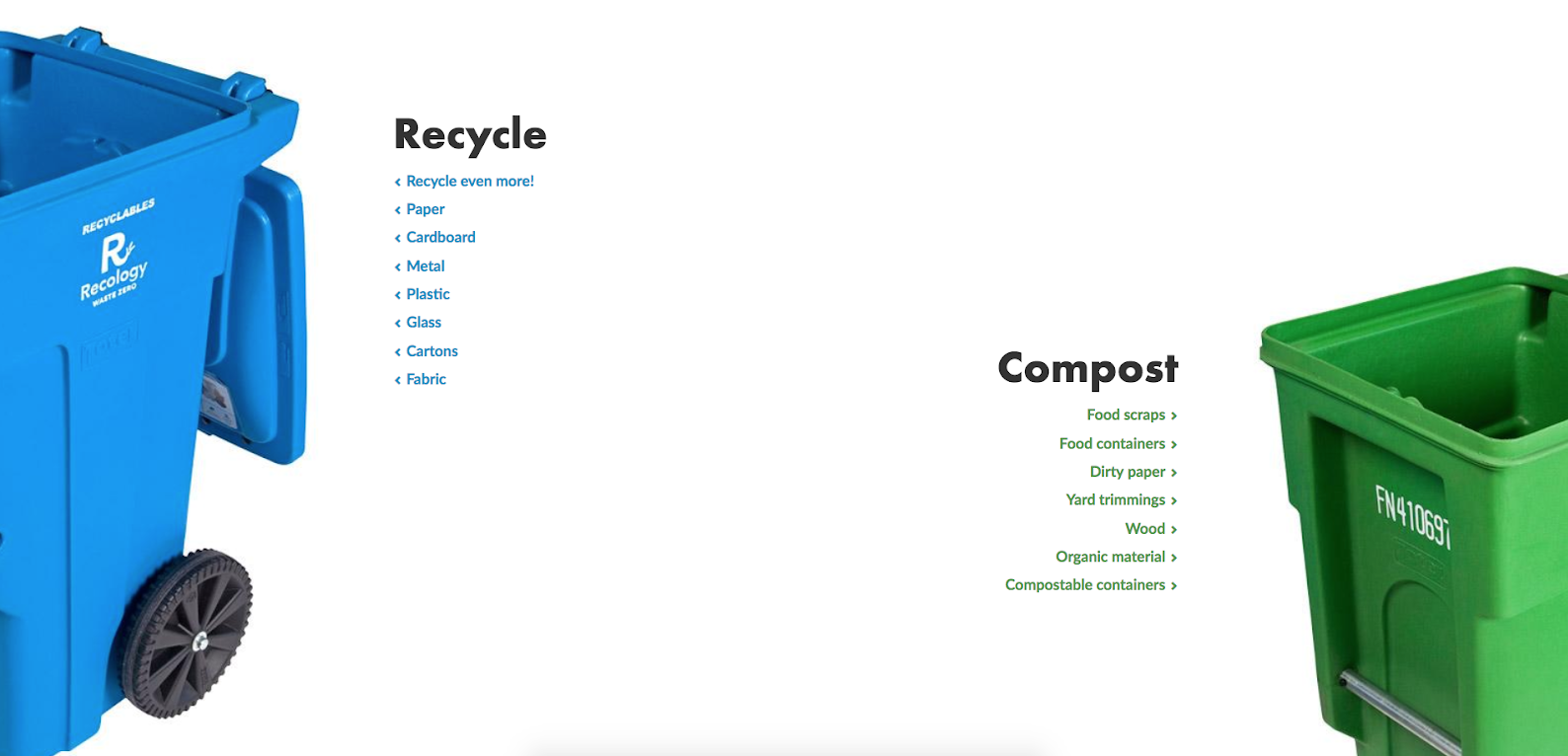

Example: San Francisco’s recycling page understands the limited attention span of internet users by directing the eyes to the desired action. They use white space (or negative space) to turn the user’s attention to the desired actions.

Example: San Francisco’s recycling page understands the limited attention span of internet users by directing the eyes to the desired action. They use white space (or negative space) to turn the user’s attention to the desired actions.

#6 Loss Aversion

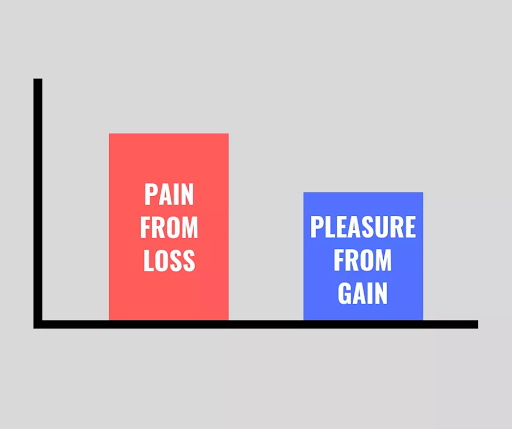

People have, perhaps unsurprisingly, an intrinsic disdain for loss. This makes sense. Most people aren’t in favor of losing something. We get attached. And we hold onto that attachment — be it emotional, relational, physical or spiritual. So, how do we communicate our climate and sustainability work in such a way that it’s mindful of the public’s proclivity for averting or avoiding loss? When we think about what people care about — quality of life, standard of living, ego, money, health, and physical security — are we articulating our work in such a way that is mindful of what they don’t want to lose?

People have, perhaps unsurprisingly, an intrinsic disdain for loss. This makes sense. Most people aren’t in favor of losing something. We get attached. And we hold onto that attachment — be it emotional, relational, physical or spiritual. So, how do we communicate our climate and sustainability work in such a way that it’s mindful of the public’s proclivity for averting or avoiding loss? When we think about what people care about — quality of life, standard of living, ego, money, health, and physical security — are we articulating our work in such a way that is mindful of what they don’t want to lose?

Habitat or species loss quickly translates here — as does the quality of life lost, the money lost, the health lost and the security lost from fossil fuels, global heating, and extreme weather — but do we also build new attachment to the kind of world we’re trying to build? For example, after a city turns a few previously road-trafficked blocks into a pedestrian-only zone, full of beautiful park amenities, and encourages active public engagement in that new space, it’s much more likely that the public will become attached to this new reality and want to preserve, protect and proliferate the experience elsewhere.

How do we show that life is better in this new greener world? How do we give people an experience that fosters attachment to that new and better life? There’s a lot of natural, intrinsic fear in letting go of the known fossil-fueled experience. One way to offset this fear is to provide experiences for people to build new attachment to the new reality that we’re trying to create. Give them something to hold onto, to protect. Most people who have a personal experience and bond with something that’s impacted by global heating — a polar bear, a vulnerable community, a seaside view — are more likely to do everything they can to protect it. In our messaging and mobilizing, let’s give them something specific to protect.

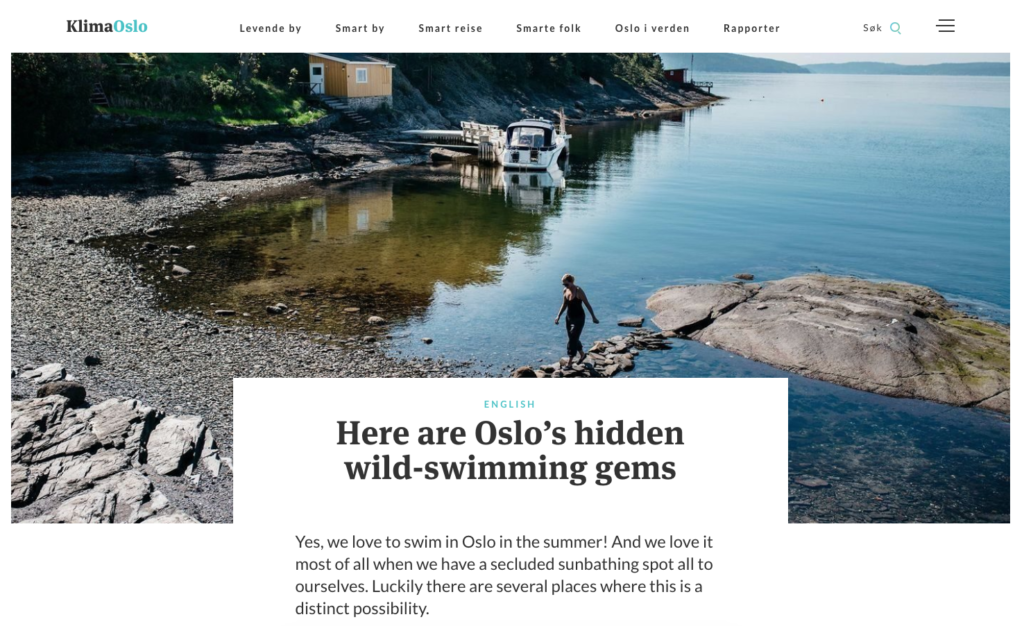

Example: Oslo’s climate website talks first about hidden swimming gems as a way of discussing the importance of protecting water quality. The webpage doubles down on the emotional attachment so that the user will then want to avoid the loss (of these swimming gems) that could result from poor water quality.

Example: Oslo’s climate website talks first about hidden swimming gems as a way of discussing the importance of protecting water quality. The webpage doubles down on the emotional attachment so that the user will then want to avoid the loss (of these swimming gems) that could result from poor water quality.

#7 Primacy Bias

There is a bias towards information that’s presented first, versus information that’s less visible. How does that bias impact how we message climate and sustainability, then? Is it presented in a highly visible way on our websites and do we have social media channels specifically devoted to our climate and sustainability work (to send a message to the public that this is a priority)? Are our local leaders (e.g. mayors, city staff) leading with the climate and sustainability message or are they presenting it as part of a whole portfolio and placing it last on a list?

There is a bias towards information that’s presented first, versus information that’s less visible. How does that bias impact how we message climate and sustainability, then? Is it presented in a highly visible way on our websites and do we have social media channels specifically devoted to our climate and sustainability work (to send a message to the public that this is a priority)? Are our local leaders (e.g. mayors, city staff) leading with the climate and sustainability message or are they presenting it as part of a whole portfolio and placing it last on a list?

Exercise: Mindful of primacy bias, it’s worth scanning communication vehicles and channels to see if climate and sustainability are presented prominently and if not, is that negotiable at all within the city/town/organization? How can we inch up the climate and sustainability offerings so that, from a behavior change communications perspective, we’re on the top, not the bottom, of any list?

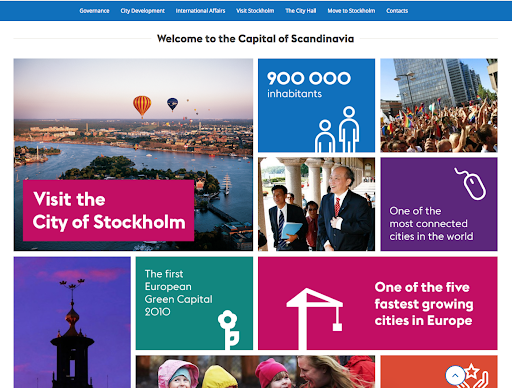

Example: See how Stockholm presents itself to the world in this picture. On the landing page, it prioritizes its green leadership as one of its key selling points, alongside “most connected” and “fastest growing”. This sends the message to the world that being a “green capital” is an enduring priority and selling point for Stockholm.

Example: See how Stockholm presents itself to the world in this picture. On the landing page, it prioritizes its green leadership as one of its key selling points, alongside “most connected” and “fastest growing”. This sends the message to the world that being a “green capital” is an enduring priority and selling point for Stockholm.

#8 Procrastination

Everyone procrastinates on something at some point in their day, week, or month, which is why any far-off “2050” framing for our climate and sustainability initiatives is potentially problematic. Even 2040 and 2030 seem far off. People will wait until the last minute to do whatever it is we’re asking them to do. It’s also why it’s problematic for us to talk about future impacts; it merely reinforces the proclivity to procrastinate. We need to talk about impacts that are happening here and now. We need to offer easy, bite-sized baby steps that anyone can take now. And we need public-friendly, short-term climate goals and deadlines to balance our plethora of long-term climate goals.

Everyone procrastinates on something at some point in their day, week, or month, which is why any far-off “2050” framing for our climate and sustainability initiatives is potentially problematic. Even 2040 and 2030 seem far off. People will wait until the last minute to do whatever it is we’re asking them to do. It’s also why it’s problematic for us to talk about future impacts; it merely reinforces the proclivity to procrastinate. We need to talk about impacts that are happening here and now. We need to offer easy, bite-sized baby steps that anyone can take now. And we need public-friendly, short-term climate goals and deadlines to balance our plethora of long-term climate goals.

People are more likely to take action now if it’s easy now, they can see the difference now, and the goals are relevant now. Admittedly, the short-term climate/sustainability ask doesn’t always have the most visible returns, but we do need to refocus our communications and public engagement lenses on the 2020 and 2025 realities so that people’s penchant for procrastination is countered by near-term realities and possibilities.

Example: Boulder’s “Four Actions with Impact” aims to get people moving now with simple actions they can take now. The videos show normal residents taking simple actions in four areas. This helps the user feel like it can be done, that it’s pragmatic and possible, and helps prevent the procrastination that often comes with climate action due to feelings of overwhelm or inefficacy.

Example: Boulder’s “Four Actions with Impact” aims to get people moving now with simple actions they can take now. The videos show normal residents taking simple actions in four areas. This helps the user feel like it can be done, that it’s pragmatic and possible, and helps prevent the procrastination that often comes with climate action due to feelings of overwhelm or inefficacy.

#9 Social Norms

We all know the power of social norming something. Approval matters. What others are doing matters. We all know the study that shows that if your neighbor has solar panels, you’re more likely to get solar panels. And if your neighbor is saving money on their utility bill, due to some energy efficiency measures, you’re more likely to be compelled to pursue the same or better savings by taking similar action. Given this, how can we better use our communication vehicles to show that a movement is happening and that our public and private sectors are changing the game and making the shift? How are we reflecting back community actions so that residents and building owners see their peers taking action across the community and are thus motivated to do what others are doing?

We all know the power of social norming something. Approval matters. What others are doing matters. We all know the study that shows that if your neighbor has solar panels, you’re more likely to get solar panels. And if your neighbor is saving money on their utility bill, due to some energy efficiency measures, you’re more likely to be compelled to pursue the same or better savings by taking similar action. Given this, how can we better use our communication vehicles to show that a movement is happening and that our public and private sectors are changing the game and making the shift? How are we reflecting back community actions so that residents and building owners see their peers taking action across the community and are thus motivated to do what others are doing?

This involves storytelling and the use of photography and video and so we recognize that it’ll take time to present a picture of what the new (green) social norm is within the community. But it’s worthwhile because it works. Reflecting back to the community the green actions happening within the community not only works from a social norming perspective but especially in the field of climate action and climate policy, where people can feel like their individual action won’t make a big difference, this reflecting back can also lift people up emotionally, provide inspiration and hope, and counteract defeatism.

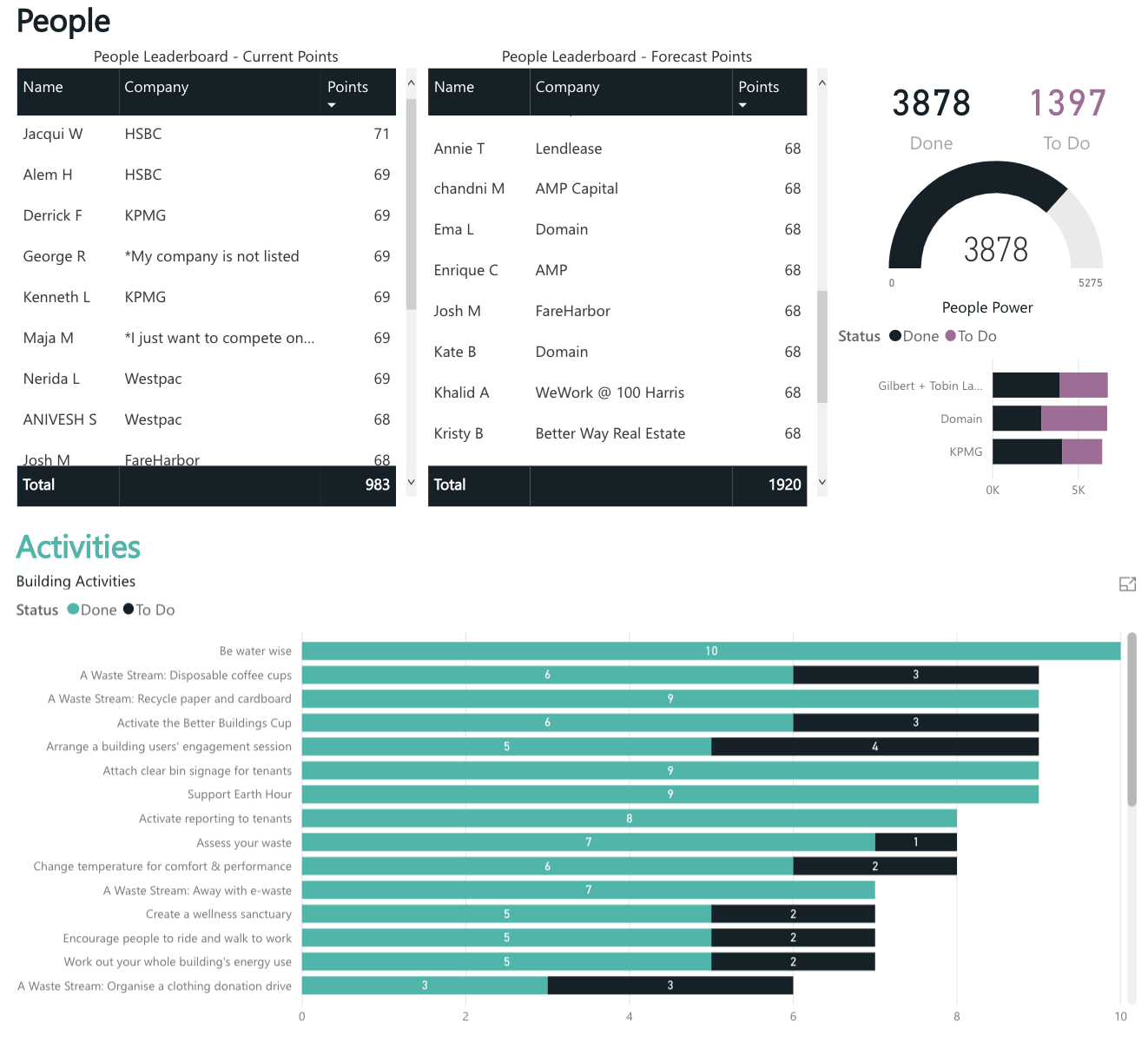

Example: Sydney, in its partnership with the Better Buildings Cup, is working to create social norms for greener living and greener buildings. By creating competitions that track waste and energy management and then mirror back the results and the winners on their media channels, this effort is conveying to the public that many people are doing this and, thus, so should you. Their sites show lots of activity in this space, show people having fun, and show plenty of diversity (in action taken and persons taking action) so that the user feels represented in this space.

Example: Sydney, in its partnership with the Better Buildings Cup, is working to create social norms for greener living and greener buildings. By creating competitions that track waste and energy management and then mirror back the results and the winners on their media channels, this effort is conveying to the public that many people are doing this and, thus, so should you. Their sites show lots of activity in this space, show people having fun, and show plenty of diversity (in action taken and persons taking action) so that the user feels represented in this space.

#10 Status Quo Bias

Default settings are powerful. We like routine and we stick to our routines. Similarly, if a status quo has already been established, we’re less likely, in general, to deviate from that. It’s just easier that way. So, how does this principle and psychology impact our climate-focused behavior change communications?

Default settings are powerful. We like routine and we stick to our routines. Similarly, if a status quo has already been established, we’re less likely, in general, to deviate from that. It’s just easier that way. So, how does this principle and psychology impact our climate-focused behavior change communications?

First of all, are we reaching people within their routine, versus asking them to find us, which is often outside of their routine? Are we meeting them with our messages and messengers and going to where their routines take them? If not, let’s start doing that. Also, how do we start setting up default settings that are more sustainable? We already know what’s possible with opt-out or opt-in framing (the former produces significantly higher participation rates than the latter), but how can we take this further so that the new status quo is increasingly sustainable?

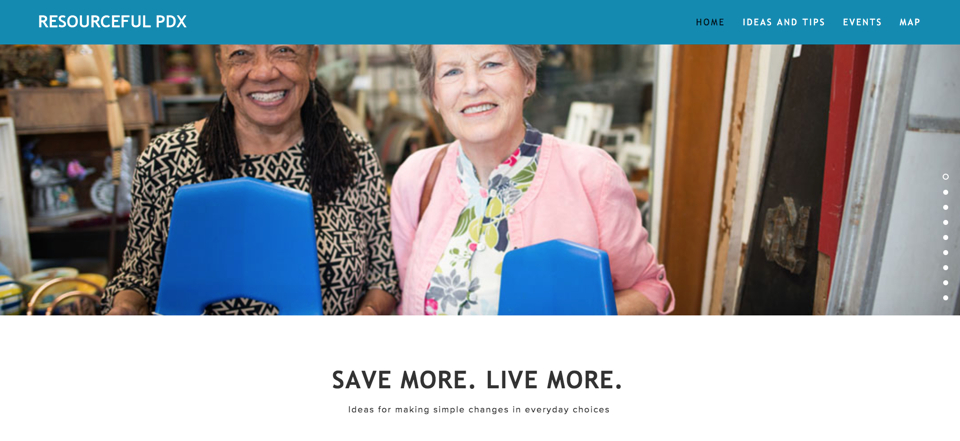

Example: This Portland partnership presents “ideas for making simple changes in everyday choices”. No big leaps here. It’s about living more and saving more. This is something people can stomach and it understands people’s proclivity for keeping the status quo. It gets a foot in the behavioral door with small bite-sized steps.

Example: This Portland partnership presents “ideas for making simple changes in everyday choices”. No big leaps here. It’s about living more and saving more. This is something people can stomach and it understands people’s proclivity for keeping the status quo. It gets a foot in the behavioral door with small bite-sized steps.

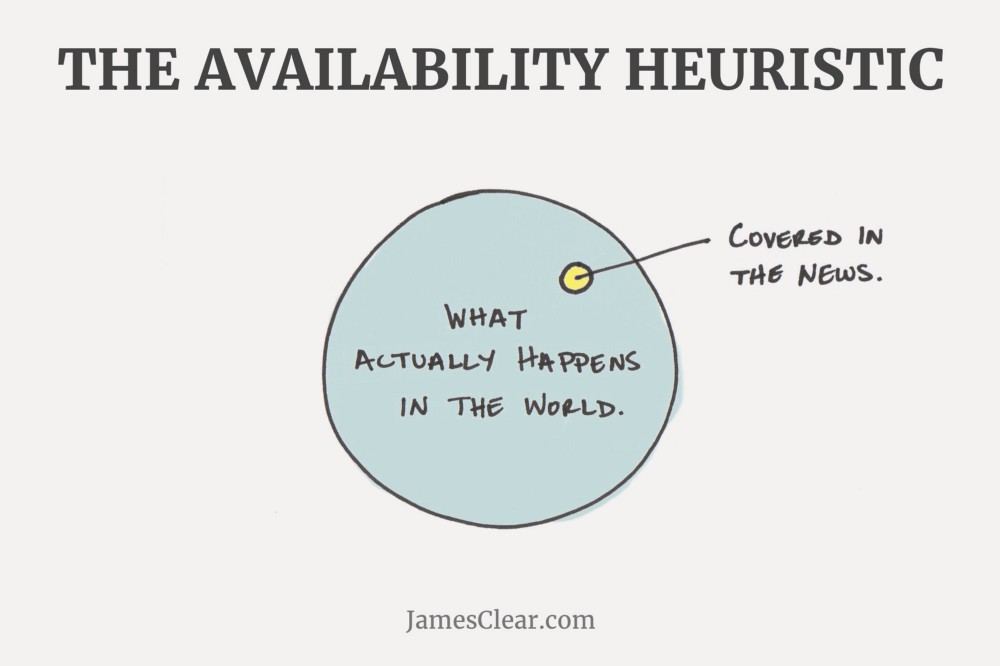

#11 The Availability Heuristic

Our publics may think they’ve never experienced a climate impact before, or if they have there’s only been a few events, not many. This is due, in part, to the fact that the press and policymakers aren’t contextualizing extreme weather events within a global warming reality. And so the availability of our climate memory, and how easily things come to mind where the climate dots are connected, is limited. This is a problem because, as Ideas42 put it, “we judge probabilities based on how easily examples come to mind.”

Our publics may think they’ve never experienced a climate impact before, or if they have there’s only been a few events, not many. This is due, in part, to the fact that the press and policymakers aren’t contextualizing extreme weather events within a global warming reality. And so the availability of our climate memory, and how easily things come to mind where the climate dots are connected, is limited. This is a problem because, as Ideas42 put it, “we judge probabilities based on how easily examples come to mind.”

How are we communicating and chronicling for our communities the repeated climate impacts so that the public is able to calculate more realistic probabilities because examples are more available to the mind? Can we use our media channels — our websites, our social media — to document the climate impacts so that people have a more realistic assessment of probability? Similarly, how are we showcasing solutions (in every possible way, and repeatedly) so that people have constant and common examples of the kind of behavior we’re encouraging. So that when they think of “going green”, there are plenty of highly public examples that come to mind, stuff they’ve seen and witnessed before.

The more we individually and organizationally message this — so that the public is seeing its leaders going green, too, in what they eat, drive, fly, wear and power — the more the public has these available examples for mental and memory recall.

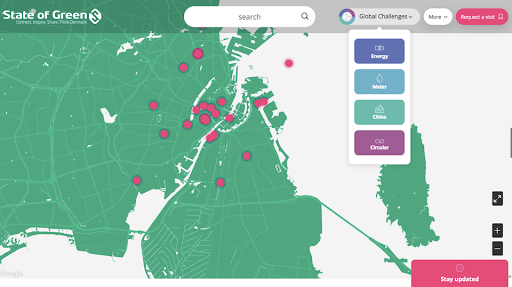

Example: Copenhagen’s partnership with “State of Green” to showcase the green initiatives happening across the city helps the user feel that there’s a lot happening. This site is presenting back to the community all of the activity in the climate space so that there’s ample available evidence and data for resident learning and discovering.

Example: Copenhagen’s partnership with “State of Green” to showcase the green initiatives happening across the city helps the user feel that there’s a lot happening. This site is presenting back to the community all of the activity in the climate space so that there’s ample available evidence and data for resident learning and discovering.

#12 The Planning Fallacy

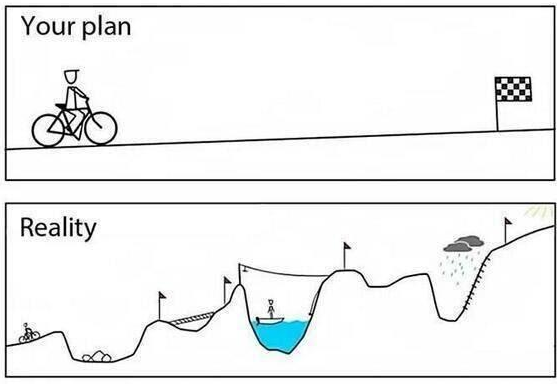

Humans rarely account for and allocate sufficient time for a given task. In study after study, we’re overly optimistic about how much time it will take to accomplish a specific task. This has huge implications on any of our sustainability targets and timelines for 2030, 2040 and 2050 and why it is essential to be very clear about how much time these tasks will take and to reorient the deadlines so that it’s an easier estimable planning period for the public (since we aren’t often planning other tasks in 20 or 30 year timeframes). Admittedly, since large-scale game-changing will take time, we want to both clear about the necessary planning and positive about our ability to accomplish the task so that the public isn’t overwhelmed by the amount of time needed.

Humans rarely account for and allocate sufficient time for a given task. In study after study, we’re overly optimistic about how much time it will take to accomplish a specific task. This has huge implications on any of our sustainability targets and timelines for 2030, 2040 and 2050 and why it is essential to be very clear about how much time these tasks will take and to reorient the deadlines so that it’s an easier estimable planning period for the public (since we aren’t often planning other tasks in 20 or 30 year timeframes). Admittedly, since large-scale game-changing will take time, we want to both clear about the necessary planning and positive about our ability to accomplish the task so that the public isn’t overwhelmed by the amount of time needed.

In behavior change communications, we’ll want to give examples of similar time requirements (associated with other behaviors in their lives) so that any green initiative we’re requesting has a salient comparison. A failure to do this could backfire. As New York Times columnist David Brooks put it, people “have developed an absurd view of the power of government. Many voters seem to think that government has the power to protect them from the consequences of their sins. Then they get angry and cynical when it turns out that it can’t.”

Helping our communities know how much planning is required to make the necessary shifts may be helpful, then, in setting expectations. And doing it in shorter increments (versus 2050 timeframes) may be useful in making sure those expectations are realistic, the short-term planning is reported and made public, and everyone is witnessing what’s involved.

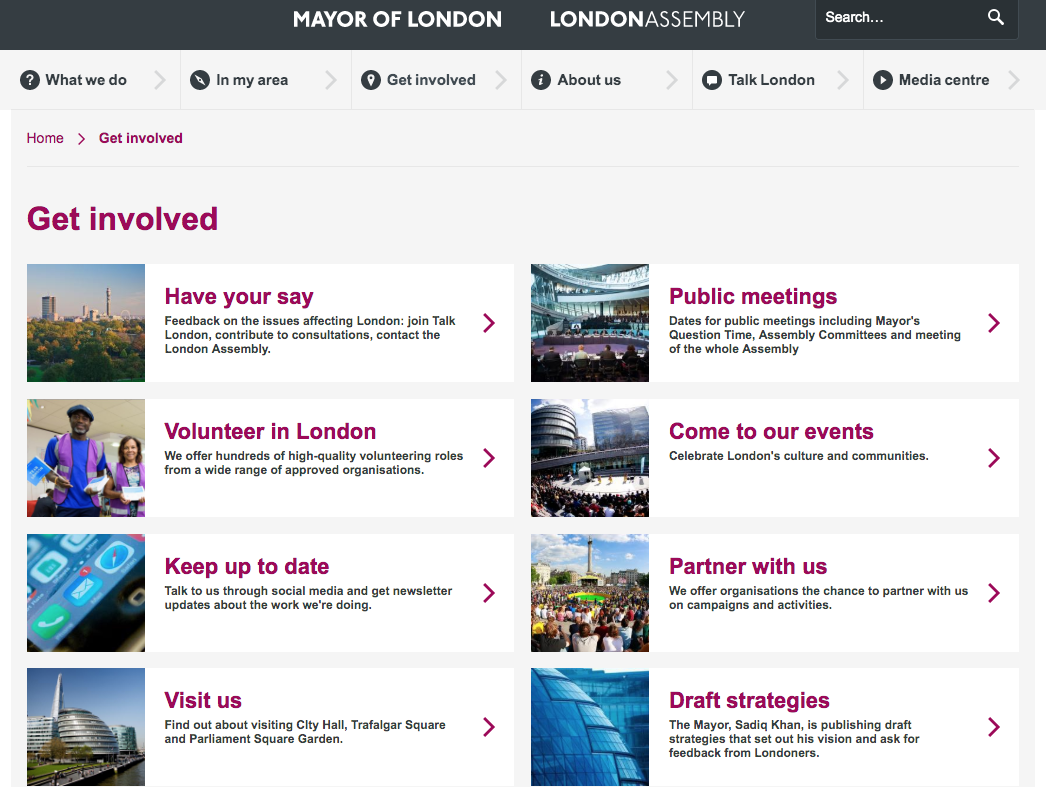

Example: London provides ample options, which appeals to citizens of all sorts. It gives multiple time-sensitive and time-specific actions so that people can participate based on the time they have available to them. And we know that once we get them involved in one thing they’re more likely to take action in other areas.

Example: London provides ample options, which appeals to citizens of all sorts. It gives multiple time-sensitive and time-specific actions so that people can participate based on the time they have available to them. And we know that once we get them involved in one thing they’re more likely to take action in other areas.

Next Steps

I encourage you to check out Ideas42’s full explanation and articulation of these 12 principles and psychologies (they’ve got all of the study/research links for further sourcing and citing). I’ve hyperlinked each page here for quick retrieval of each section.

1. Choice overload

2. Cognitive depletion & decision fatigue

3. Hassle factors

4. Identity

5. Limited attention

6. Loss aversion

7. Primacy bias

8. Procrastination

9. Social norms

10. Status quo bias

11. The availability heuristic

12. The planning fallacy

Some, or all of it, will likely be very familiar to you and, hopefully, a helpful reminder as we work to improve our behavior change communications and roll out our technical game changers. Good luck going forward!

Michael Shank, PhD, is the communications director for the Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance and adjunct faculty at New York University’s Center for Global Affairs.